PAIN AT THE FRONT OF MY KNEE – WHAT CAN I DO ABOUT IT? [PART 2]

atellofemoral joint pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common condition; where pain is felt around, behind or under the kneecap. For more about what this condition is; read our Part 1 article. Here is the link: https://continuumphysiotherapy.com.au/pain-at-the-front-of-my-knee-what-is-it-part-1/

The focus of this article is to provide tips on how to minimise your risk of this knee pain occurring, recurring or how to help rehabilitate this. It’s important to say from the outset that for this condition, PFPS, surgery is unlikely to help your knee pain.

KEYS TO THE MANAGEMENT OF PFPS:

TIP #1: IF YOU THINK YOU HAVE PFPS; SEEK HELP.

- If you are experiencing pain at the front of the knee; it is recommended to be assessed by a physiotherapist who can provide individualised recommendations based on your problem.

- This will improve your chances of a successful recovery.

TIP #2: ACTIVITY MODIFICATION

- Appropriately modifying the activities that aggravate this knee pain (e.g. squatting, running, jumping) is an important place to start.

- This may not mean completely stopping an activity or exercise altogether; but it may mean discussing with your physiotherapist what’s an appropriate and safe amount of loading of the knee to undergo.

TIP #3: GRADUALLY INCREASE YOUR ACTIVITY

- The ‘Too Much Too Soon’ approach is often a common cause for the development of PFPS.

- Large and rapid spikes in load can be problematic for the knee; whether that be the time spent participating in an activity, the duration or a new type of activity.

- Slowly increase the amount of exercise you do; for example an increase of 10% per week.

- E.g. If you ran 2 kilometres twice per week (and your goal is to run 5 kms); then the following week run 2.2 kilometres per session

- If the knee pain lasts for 24 hours or more after the exercise; then consider decreasing either the time/distance spent exercising or the intensity (for example rather than running 4 minutes per kilometre pace consider slowing this to 4 and half minutes per kilometre – that is if the speed affects your pain).

TIP #4: STRENGTHENING IS KEY

- A recent consensus statement from a panel of PFPS experts concluded that exercise has the “largest body of evidence supporting its use to improve pain and function in the short, medium and long terms” (2). This expert panel concluded that “exercise therapy remains the intervention of choice for PFPS”.

- As mentioned in the Part 1 article; commonly the quadriceps muscle group is seen to be noticeably weak which can contribute to knee pain developing (3). Strengthening the quad muscles is important.

- Quadriceps strengthening: initially, to minimise aggravating your knee pain, this might mean performing exercises in a “non weight-bearing” position such as a leg extension machine at the gym or with a theraband. Gradually progressing to more weight-bearing exercises, such as step-ups and several squat variations are good ways to strengthen the quads (see image #4).

- Research has also shown that those with PFPS display hip and trunk muscle weakness (3). Initially performing exercises such as glute bridges, side lifts and planks/side planks are good early options. Progressing to exercises such as crab walks, split squats and single leg deadlifts (see image #3) are other options to strengthen.

- If you are unfamiliar with any of these exercises; it is best to seek a professional on the correct technique of how to perform them.

TIP #5: MOVEMENT RETRAINING

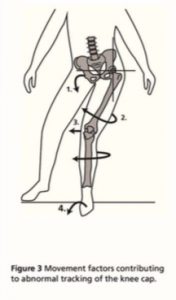

- Biomechanics of the hip and pelvis can increase load towards the knee. See the below image (image #5) for a better visual of what can often occur causing excessive load to the knee. Applying the below suggestions to your walking, standing and running can reduce load to the knee.

- 1. REDUCE HOW MUCH YOUR OPPOSITE HIP DROPS

- 2. REDUCE HOW MUCH YOUR HIP ROLLS IN

- 3. REDUCE HOW MUCH YOUR KNEE COLLAPSES IN

Image #5: demonstrating how the pelvis, hip, knee and foot/ankle biomechanics can increase load to the patellofemoral joint (1).

TIP #6: TAPING AND BRACING

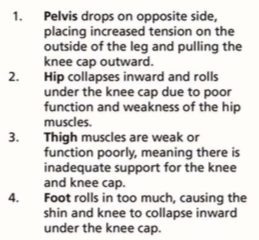

- Taping the knee to control how much the patella moves, particularly limiting movement of the kneecap towards the outside of the thigh has been shown to provide short-term relief of knee pain in this condition (2).

- There is no research evidence to support the use of taping beyond 12 months for adults with PFPS (2).

- Taping may mean that you can perform the exercises more comfortably.

- Speak with a physiotherapist about the option of taping for your knee pain.

TIP #7: SHOE INSERTS

- It has been shown that at least 1 in four people with PFPS respond positively to a shoe insert e.g. prefabricated “off the shelf” orthotics for short-term pain relief (2, 4).

- There is no research evidence supporting the use of custom-fabricated foot orthotics (made from a 3D representation of an individual’s foot) (2)

- Simply test them by performing an activity (such as squatting) that aggravates your pain; then reassess the movement with shoe inserts and if less pain –> get them, if the pain is unchanged or worse –> don’t get them.

- Remember, this has only been shown to have a short-term effect in reducing pain and is not recommended as a long term strategy.

In summary, prolonged rest and/or surgery is unhelpful to the improvement of PFPS. Exercise therapy (involving strengthening of the quadriceps, hip and trunk muscles) has been shown to be the most beneficial treatment for PFPS. Considering activity modification and a gradual increase in activity are also important in the rehabilitation or attempted prevention of this condition.

References

(1) Barton, C. J., & Rathleff, M. S. (2016). ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’: the creation of an education leaflet for patients. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 2(1), e000086.

(2) Collins, N. J., Barton, C. J., van Middelkoop, M., Callaghan, M. J., Rathleff, M. S., Vicenzino, B. T., … & de Oliveira Silva, D. (2018). 2018 Consensus statement on exercise therapy and physical interventions (orthoses, taping and manual therapy) to treat patellofemoral pain: recommendations from the 5th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Gold Coast, Australia, 2017. Br J Sports Med, bjsports-2018.

(3) Powers, C. M., Witvrouw, E., Davis, I. S., & Crossley, K. M. (2017). Evidence-based framework for a pathomechanical model of patellofemoral pain: 2017 patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester, UK: part 3. Br J Sports Med, 51(24), 1713-1723.

(4) Collins, N., Crossley, K., Beller, E., Darnell, R., McPoil, T., & Vicenzino, B. (2008). Foot orthoses and physiotherapy in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome: randomised clinical trial. Bmj, 337, a1735.