Making Sense of Pain (Part 1)

What is pain?

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” (1) Importantly, pain itself is a personal experience. The actual process in our nervous system where messages are being sent to our brain about damage or the threat of damage is called nociception. Nociception and pain are not the same. Another way to think about it would be if both you and a friend walked across hot coals. It would likely be painful for both you and your friend, but you would both experience this pain differently. Pain that a person experiences is influenced by various biological, psychological, and social factors. Perhaps your friend has walked across hot coals before so they already know what to expect; perhaps everyone you know that has walked across hot coals before has warned you about how painful it is; or perhaps a house burnt down in your neighborhood as a child and you have flashbacks of this event whenever you see fire. Just as these factors can influence one’s experience of pain, the experience of pain itself can also have lasting effects on a person’s function, social and psychological well-being, particularly when this pain becomes chronic.

What does it mean when pain is chronic?

Chronic pain is pain that has been present for >3 months, and is associated with emotional distress and functional disability (2). In chronic pain, nociception is altered due to a number of changes that take place over time in our nervous system that increase the sensitivity of nerves in our brain and spinal cord (central sensitization), as well as our skin and other tissues (peripheral sensitization). The resulting pain is called “nociplastic pain” and is defined as “pain that emerges from altered nociception despite no evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage.” (3)

Hang on a minute … How can someone have pain with no actual tissue damage or threat of tissue damage?

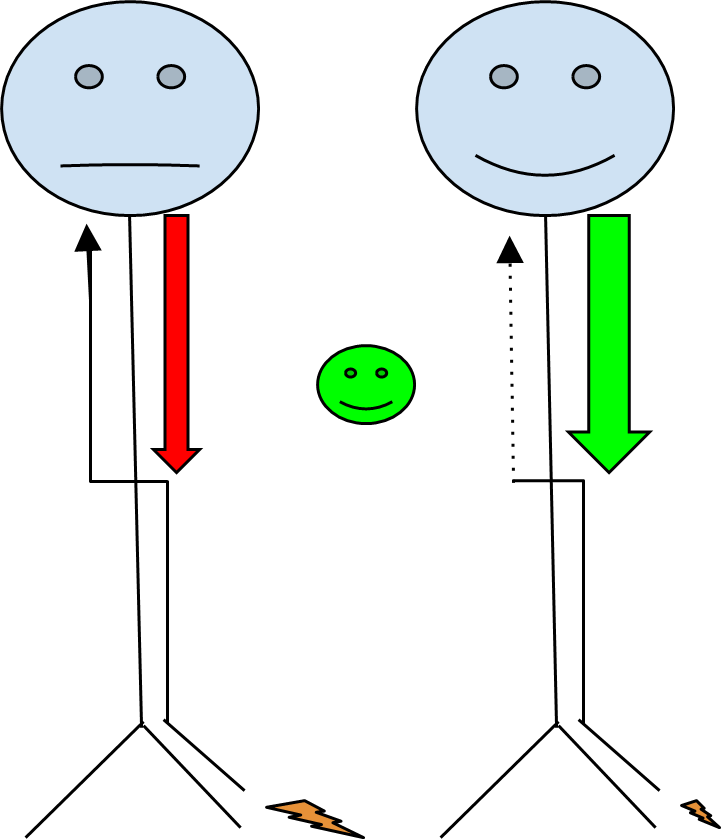

The answer starts with the underlying mechanisms that lead to a sensitised nervous system. In acute pain, or when pain has been present for less than 3 months, tissues are sensitised and pain signals are sent to the spinal cord and then up to the brain to interpret these messages. The brain can then send messages back down the spinal cord telling the body that things are okay, and to reduce or stop these pain signals. This is called “descending pain modulation.” (4)

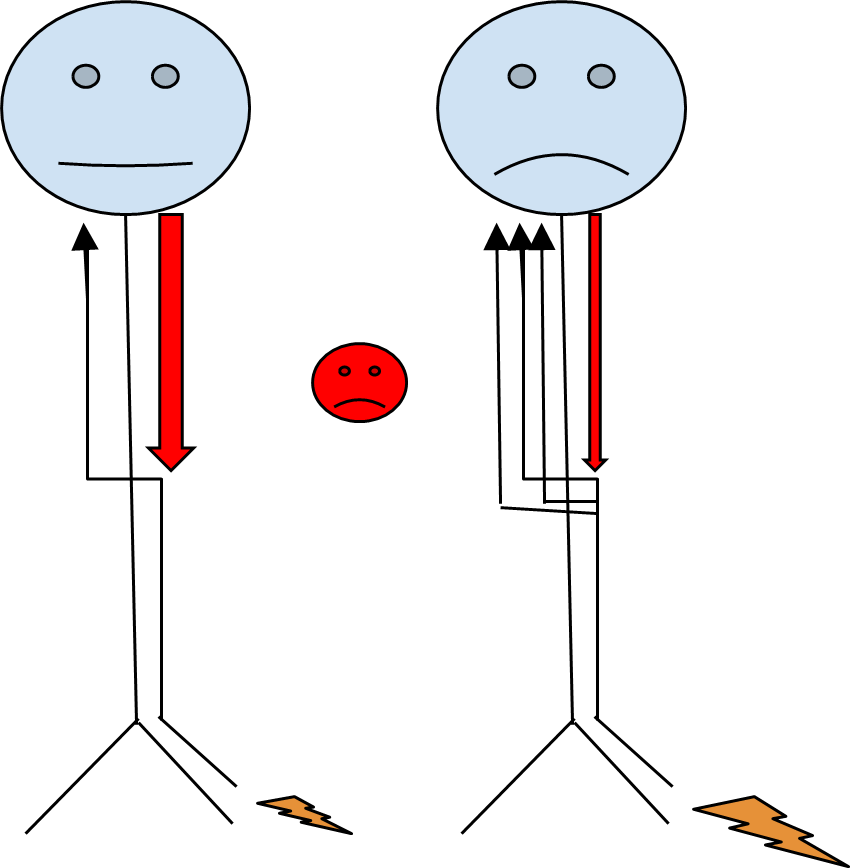

In chronic pain, pain signals are sent to the spinal cord and brain in the same way as in acute pain. However, descending pain modulation is altered over time, and the brain either does not tell the body to stop sending signals, or the brain does not think that the danger has gone away (4). With this, the frequency of pain signals being sent from the spinal cord to the brain increases, and over time nerves in the spinal cord become more sensitised. This is called “central sensitisation.” As a result, pain signals continue to be sent to the brain when there is either little to no stimulus, or the amount of pain signals are exaggerated in response to a normal painful stimulus.

So if I have chronic pain, does this mean it’s all in my head?

NO!

The pain is very real, and there are definite physical changes that take place in the nervous system at a cellular level. Combined with various individual psychological and social factors, every person’s pain experience is unique and should be taken seriously. The challenge with chronic pain and central sensitisation is addressing the whole pain experience, and not just looking for something broken to fix.

Stay tuned for the next article in this series, which will discuss strategies to manage chronic pain, and explore how to best settle down a sensitized nervous system.

Are you experiencing pain? Hit the ‘Book Now’ button below to book a time for physiotherapist’s so that we can offer help to you.

REFERENCES

- Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe FJ, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, Song XJ, Stevens B, Sullivan MD, Tutelman PR, Ushida T, Vader K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020 Sep 1;161(9):1976-1982.

- Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Giamberardino MA, Goebel A, Korwisi B, Perrot S, Svensson P, Wang SJ, Treede RD; IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):28-37.

- Kosek E, Clauw D, Nijs J, Baron R, Gilron I, Harris RE, Mico JA, Rice ASC, Sterling M. Chronic nociplastic pain affecting the musculoskeletal system: clinical criteria and grading system. Pain. 2021 Nov 1;162(11):2629-2634.

- Ossipov MH, Morimura K, Porreca F. Descending pain modulation and chronification of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2014 Jun;8(2):143-51. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000055. PMID: 24752199; PMCID: PMC430141