PAIN AT THE FRONT OF MY KNEE – WHAT IS IT? [PART 1]

Pain experienced at the front of the knee affects those who are physically active and inactive (1). A common source of pain felt at the front of the knee arises from the ‘patellofemoral joint’ – this is the joint where the kneecap bone (patella) and the bottom of the thigh bone (femur) make contact. Patellofemoral joint pain syndrome (PFPS) accounts for 16.5% of all consultations in sports medicine clinics (2). It’s important to note early that there can be other structures of the knee that can contribute to pain – however this article will focus on PFPS.

People with PFPS commonly describe a gradual onset of pain, not usually related to trauma, but typically due to a significant increase in activity that loads the patellofemoral joint (such as squatting, climbing stairs, running, hiking) (4). Pain is felt around, behind or under the kneecap.

Activities that often aggravate the knee include rising from sitting, squatting, going up and downstairs (1) as well as commonly seen in runners (3). In some cases PFPS can persist for many years and can cause a decrease in sports participation (1); this can lead to weight gain resulting in greater loads at the patellofemoral joint and knee pain, triggering a “vicious cycle” that can further act as a barrier to partaking in physical activity (4).

PFPS can be encountered during the adolescent age, which is particularly seen during periods of rapid growth (5). It is also seen in older adults; 70% of those aged 40 and older with PFPS had osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint as shown on x-ray scans (6,7). It affects both males and females at all activity levels (19).

What is happening at my knee that is making me feel pain?

Amongst all the research literature there is some evidence to suggest more than one structure contributes to the sensation of pain at the knee (5). Hence, PFPS is a broad term that encompasses several painful structures at the front of the knee. So what are these structures?

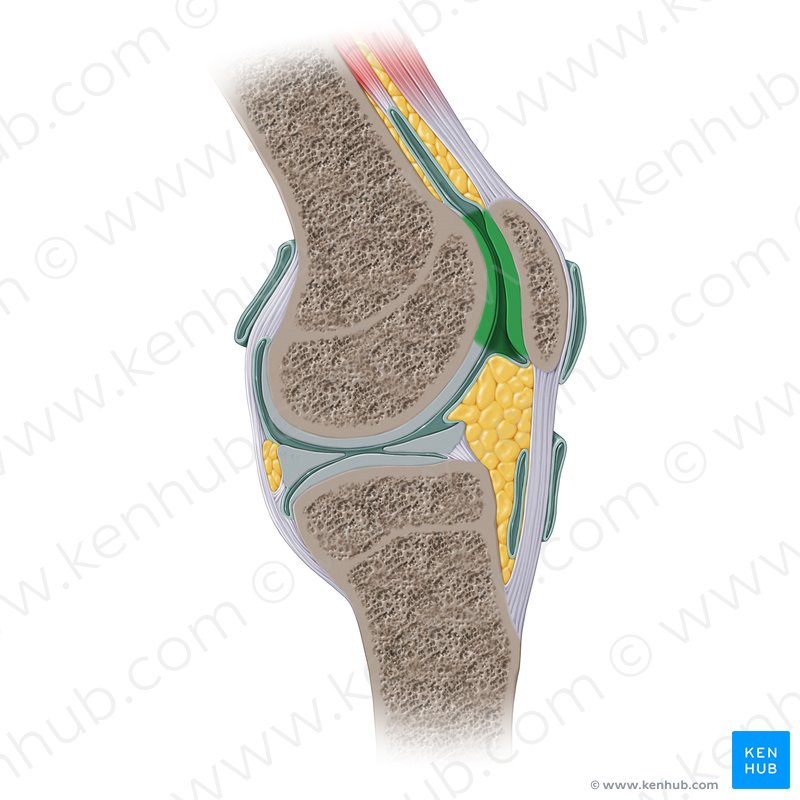

- Cartilage disruption of the patellofemoral joint and ‘bone swelling’ (known as bone marrow lesions) displayed in those with abnormal structure or alignment of the patellofemoral joint (8). (see Image #1)

- There is a small amount of research showing that structures close by to the patellofemoral joint could contribute to the pain process;

- the infrapatellar pad; a substance of fatty tissue that sits below the kneecap with a lot of nerve supply (9) (see Image #1)

- Increased water content in subchondral patellar bone (layer of bone just below the cartilage) seen in runners (10)

- Bone marrow lesions (‘bony swelling’) in those with patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis (11)

(*) Green shading demonstrating the contact surfaces of the kneecap and the bottom of the femur (patellofemoral joint).

(*) The yellow substance below the kneecap is the infrapatellar fat pad.

What causes this knee pain?

Current research suggests there are various reasons why someone may develop PFPS. Below is a list of some of the key known causes of this condition.

‘TOO MUCH TOO SOON’

- A risk factor for this condition can include an increase in activity too quickly (e.g. running, squatting, jumping) (4,19).

- This may be an increase in frequency; for example in the one week increasing basketball sessions from 2 sessions a week to 5 sessions per week.

- or a rapid spike in duration of exercise; e.g. running for 20 minutes per session each week and then the next week increasing this to a 60 minute run.

- Or a change in the type of activity; such as regularly walking on flat surfaces three times per week and then suddenly changing this to walking up and down steps three times per week.

IMPAIRED QUADRICEPS FUNCTION

- Generalised quadriceps muscle weakness (the quadriceps muscle group are at the front of the thigh) and/or atrophy (muscle wasting) is seen in those with PFPS (12).

- Some studies showing reduced activation and/or timing of the inner quadriceps muscle (vastus medialis) relative to the outside muscle (vastus lateralis) can contribute to lateral movement and tilting of the patella (13,14) – which may lead to pain felt.

ALTERED HIP AND PELVIS BIOMECHANICS

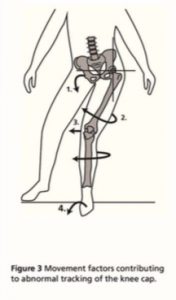

- The biomechanics of the hip joint – due to hip muscle weakness and poor function – can contribute to excessive loading of the knee → by the kneecap not tracking in it’s ‘normal groove’ and then subsequently leading to PFPS (see images #2 and #3).

- There is an association between increased hip adduction (due to the pelvis dropping on the opposite side) and the development of PFPS (15,16)

- Increased hip internal rotation was shown to be associated with PFPS in runners (16).

DECREASED HIP MUSCLE STRENGTH

It has been shown that those with PFPS had decreased strength into hip extension, abduction and external rotation (17,18); i.e. “weak glute muscles”.

EXCESSIVE FOOT PRONATION

Those with PFPS have been shown to display rearfoot and forefoot varus, navicular drop and calf muscle tightness which is consistent with foot pronation (12). In lay terms, this foot pronation can mean the shin and subsequently knee can collapse inwards increasing the load. (see image #2)

Image # 2: ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’ (19)

Most of the above risk factors for PFPS are considered modifiable; which is promising that if the causes are addressed the development of this condition may be improved upon.

Click the link below to Part 2: Pain at the Front of my Knee “What Can I Do About It?”

Crossley, K. M., van Middelkoop, M., Callaghan, M. J., Collins, N. J., Rathleff, M. S., & Barton, C. J. (2016). 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 2: recommended physical interventions (exercise, taping, bracing, foot orthoses and combined interventions). Br J Sports Med, 50(14), 844-852.

Taunton, J. E., Ryan, M. B., Clement, D. B., McKenzie, D. C., Lloyd-Smith, D. R., & Zumbo, B. D. (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. British journal of sports medicine, 36(2), 95-101.

Neal, B. S., Barton, C. J., Gallie, R., O’Halloran, P., & Morrissey, D. (2016). Runners with patellofemoral pain have altered biomechanics which targeted interventions can modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait & posture, 45, 69-82.

Crossley, K. M., Callaghan, M. J., & van Linschoten, R. (2016). Patellofemoral pain. Br J Sports Med, 50(4), 247-250.

Witvrouw, E., Callaghan, M. J., Stefanik, J. J., Noehren, B., Bazett-Jones, D. M., Willson, J. D., … & Crossley, K. M. (2014). Patellofemoral pain: consensus statement from the 3rd International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013. Br J Sports Med, 48(6), 411-414.

Hinman, R. S., Lentzos, J., Vicenzino, B., & Crossley, K. M. (2014). Is patellofemoral osteoarthritis common in middle‐aged people with chronic patellofemoral pain?. Arthritis care & research, 66(8), 1252-1257.

Duncan, R. C., Hay, E. M., Saklatvala, J., & Croft, P. R. (2006). Prevalence of radiographic osteoarthritis—it all depends on your point of view. Rheumatology, 45(6), 757-760.

Stefanik, J. J., Zhu, Y., Zumwalt, A. C., Gross, K. D., Clancy, M., Lynch, J. A., … & Guermazi, A. (2010). Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis care & research, 62(9), 1258-1265.

Dragoo, J. L., Johnson, C., & McConnell, J. (2012). Evaluation and treatment of disorders of the infrapatellar fat pad. Sports medicine, 42(1), 51-67.

Ho, K. Y., Hu, H. H., Colletti, P. M., & Powers, C. M. (2014). Running-induced patellofemoral pain fluctuates with changes in patella water content. European journal of sport science, 14(6), 628-634.

Zhang, Y., Nevitt, M., Niu, J., Lewis, C., Torner, J., Guermazi, A., … & Felson, D. T. (2011). Fluctuation of knee pain and changes in bone marrow lesions, effusions, and synovitis on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 63(3), 691-699.

Powers, C. M., Witvrouw, E., Davis, I. S., & Crossley, K. M. (2017). Evidence-based framework for a pathomechanical model of patellofemoral pain: 2017 patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester, UK: part 3. Br J Sports Med, 51(24), 1713-1723.

Pal, S., Draper, C. E., Fredericson, M., Gold, G. E., Delp, S. L., Beaupre, G. S., & Besier, T. F. (2011). Patellar maltracking correlates with vastus medialis activation delay in patellofemoral pain patients. The American journal of sports medicine, 39(3), 590-598.

Pal, S., Besier, T. F., Draper, C. E., Fredericson, M., Gold, G. E., Beaupre, G. S., & Delp, S. L. (2012). Patellar tilt correlates with vastus lateralis: vastus medialis activation ratio in maltracking patellofemoral pain patients. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 30(6), 927-933.

Meira, E. P., & Brumitt, J. (2011). Influence of the hip on patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Sports Health, 3(5), 455-465.

Neal, B. S., Barton, C. J., Gallie, R., O’Halloran, P., & Morrissey, D. (2016). Runners with patellofemoral pain have altered biomechanics which targeted interventions can modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait & posture, 45, 69-82.

Van Cant, J., Pineux, C., Pitance, L., & Feipel, V. (2014). Hip muscle strength and endurance in females with patellofemoral pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International journal of sports physical therapy, 9(5), 564.

Prins, M. R., & Van Der Wurff, P. (2009). Females with patellofemoral pain syndrome have weak hip muscles: a systematic review. Australian journal of physiotherapy, 55(1), 9-15.

Barton, C. J., & Rathleff, M. S. (2016). ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’: the creation of an education leaflet for patients. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 2(1), e000086.

“© Kenhub (www.kenhub.com); Illustrator: Paul Kim”.