Pain At The Side Of My Hip: What Is It? What Can Be Done?

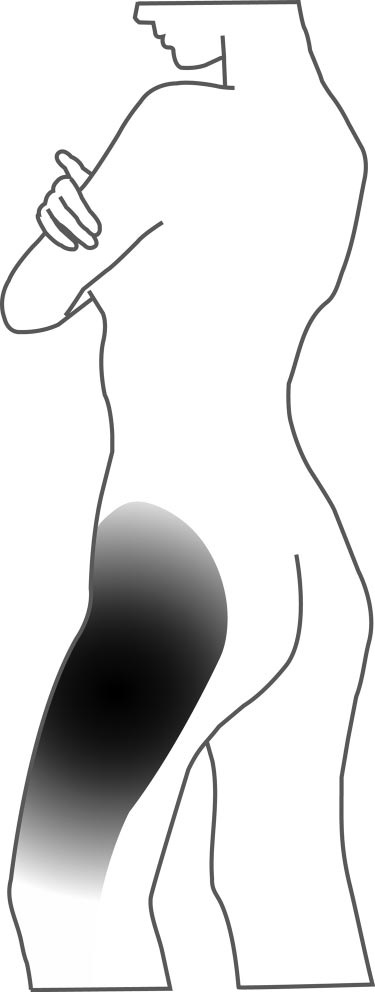

This article will focus on pain located on the side of the hip, which is commonly referred to as ‘Gluteal Tendinopathy’ or ‘Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS)’.

What are the Signs of Lateral Hip Pain?

- Pain/tenderness over the greater trochanter or ‘bony part’ of the side of the hip

- Pain when sleeping on the side and decreased quality of sleep

- Pain when standing on one leg

- Pain in tasks that require single leg weightbearing such as walking, running, stair climbing

- Pain in rising from sitting

Who does this Condition Commonly Affect?

Lateral hip pain is most common within women aged above 40 years, and can be highly associated with the physiological changes that occur as a result of menopause. This condition affects approximately 23.5% of women aged between 50 and 79 years, compared to only 8.5% of men in this age bracket (1).

It is believed that 10-25% of people experience lateral hip pain at some stage in their lifetime (2).

Overview – What is Lateral Hip Pain?

Research had previously identified the main cause of lateral hip pain to be inflammation of the bursae of the hip, known as trochanteric bursitis. The trochanteric bursa is a fluid filled sac that sits between our largest buttock muscle, the gluteus maximus, and the hip bone (greater trochanter of the femur). The bursa functions to prevent the tendon irritating our hip bone from friction (3).

More recently, research has emerged suggesting that the disease process underpinning this condition is more likely a tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendons, with approximately only 20% of presentations containing involvement of the bursa (2).

A tendinopathy refers to the structural changes that occur within a tendon in response to overuse or sudden increases in load. This disrupts the structural organisation of the tissue (collagen matrix) and leads to an increase in various molecules that cause swelling within the tendon, known as type III collagen fibres and proteoglycans (see picture below for comparison of a tendinopathy (R) vs a healthy tendon (L)). Though previously referred to as a ‘tendinitis’, research has emerged that identifies the term ‘tendinopathy’ to be a more accurate description of the condition as its focus is more on structural change within the tendon rather than inflammation (4).

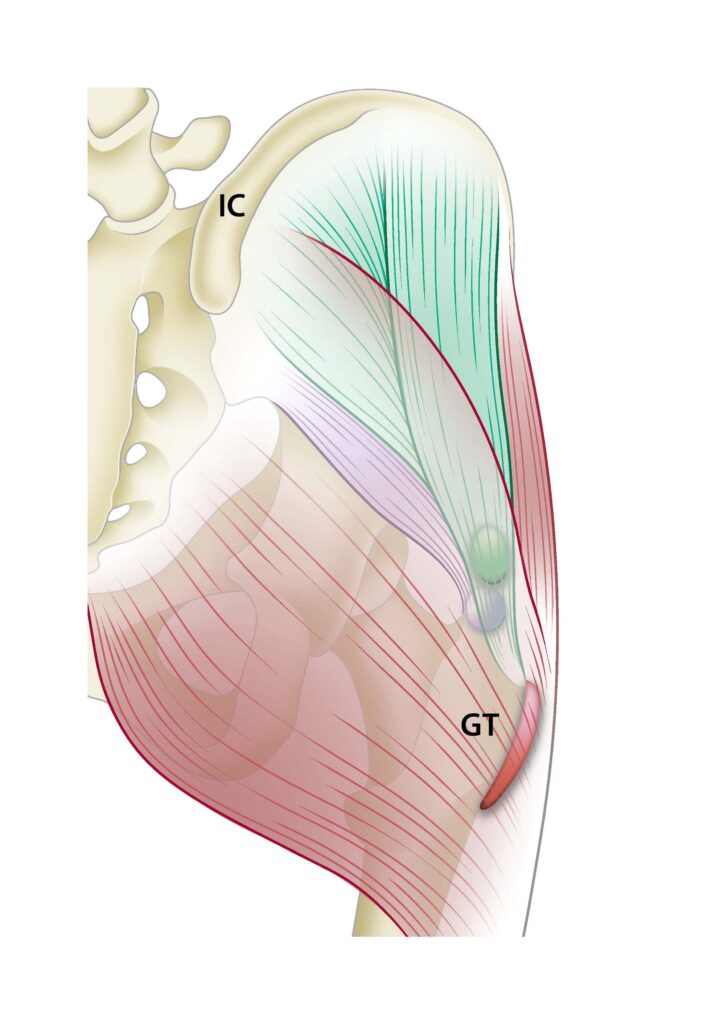

The gluteus medius and gluteus minimus can be found slightly deeper to the large gluteus maximus muscle and contain tendons that insert onto the hip bone (3) (see picture below). These muscles work to abduct the hip joint and stabilise the pelvis when weightbearing on one limb, such as running, hiking, etc. Sudden increases in these activities can provoke tendinopathy within the gluteus minimus and medius tendons, which can cause significant pain and dysfunction around the lateral hip (4).

(7)

What Causes Lateral Hip Pain?

- Sudden changes in activity levels – This condition is often seen in previously inactive people that attempt to increase their activity levels by a significant amount in a short period of time. As mentioned above, this sudden increase in activity load is the most mechanism that prompts the development of a gluteal tendinopathy (1).

- Postural habits that bring the hip into adduction – Hip adduction occurs when the leg moves towards the midline of the body (see picture below) and can be seen in a range of static standing and sitting postures, including;

- Leaning sideways into one hip when standing

- Sitting with legs crossed

- Sitting with knees together

- Crossing ankles when sitting on recliner chairs

- Sleeping on the side with the affected hip up & slightly flexed forward

Adduction of the hip places a compressive load through the glute medius and glute minimus tendons (1). Tendons typically respond poorly to compressive loading, and thus sustaining these adducted positions for an extended period of time can contribute to the development and exacerbation of gluteal tendinopathy (2).

Sitting Postures – NOT RECOMMENDED

Sitting Postures – RECOMMENDED

Standing Posture – NOT RECOMMENDED

Standing Posture – RECOMMENDED

Lying/Sleeping Positions

How can Physiotherapy help?

A key randomised controlled trial study involving 201 participants (average age 54; 82% females) with gluteal tendinopathy investigated the effectiveness of three common interventions (5). These included:

- Education + Exercise group (EDX)

- This includes 14 individual physiotherapy sessions over an 8-week period.

- Education (via handouts and DVD) was provided on tendon care and appropriate amounts of gradual progression on tendon loading.

- Home exercise program strengthening the hip abductors and dynamic control of adduction (hip/pelvic stability) during function (4-6 exercises performed daily) (see below videos 2 examples of exercises given).

- Corticosteroid (‘cortisone’) injection (CSI)

- ‘Wait and see’ approach (WS)

- 1 x session with physiotherapist providing general information about the condition, possible risk factors, advice regarding continuation of activity and reassurance that the condition resolves over time.

Results showed;

- At the 8-week mark:

- Education + Exercise Group; demonstrated a 77.3% self-reported success rate (rate of change)

- Corticosteroid injection demonstrated a 58.5% self-reported success rate (rate of change)

- Wait and See approach demonstrated a 29.4% success rate (rate of change)

- At the 52-week mark:

- Education + Exercise Group; demonstrated a 78.6% self-reported success rate (rate of change)

- Corticosteroid injection demonstrated a 58.3% self-reported success rate (rate of change)

- Wait and See approach demonstrated a 51.9% success rate (rate of change)

Participants in the EDX and CSI groups both demonstrated greater global improvement and lower pain intensity in the short term (8 weeks) than the wait and see approach. The EDX showed better outcomes at the 8-week mark compared to the CSI group which was also shown with reduced pain rating.

At the 52-week mark both the EDX and CSI groups continued to demonstrate greater global improvement than the wait and see approach; with the EDX group showing a better outcome. At the 52-week mark the pain rating scale was no different between the EDX and CSI group but better than the wait and see approach.

This study shows that education and exercise group demonstrated superior successful effects of participant’s self-reported rate of change compared to the corticosteroid injection therapy at 8 weeks and 52 weeks from the start of the intervention period. Self-rated pain was also better in the EDX group at 8 weeks than the CSI, however was comparable at the 52-week mark – the authors suggest the similarity in pain reduction between these two groups may be due to the initial lower levels of pain rated (on average of all participants was 4.9 out of 10; with 10 being severe- suggesting this study doesn’t count for those living with more severe symptoms).

Despite corticosteroid injections producing a significant reduction in pain within the first 8 weeks, this key study suggests that exercise and load modification is the most effective approach in the longer-term management of a gluteal tendinopathy. The strength component of this intervention involves strengthening of muscles around the hip and pelvic region, especially the hip abductor muscles (glute med and glute min). It additionally involves advice regarding load management and reducing compressive load through the glute med and min tendons (6).

Examples of such advice include:

- Avoidance of positions where the hip is in prolonged adduction (see list above)

- When lying on the non-affected side, place a pillow between the legs to prevent the top hip from entering an adducted position

- Avoid stretching the glute med and glute min muscles

- Avoid walking uphill

If you have been experiencing any of the signs and symptoms of lateral hip pain, our physiotherapist’s can help you. Please click on the link below to book an appointment or call us on 9455 1177.

Tielle Lyons and Luke Dowse

References:

- Grimaldi, A., Mellor, R., Hodges, P., Bennell, K., Wajswelner, H., & Vicenzino, B. (2015). Gluteal tendinopathy: A review of Mechanisms, Assessment and Management. Sports Med, 45, 1107-1119. DOI 10.1007/s40279-015-0336-5

- Ganderton, C., & La Trobe University degree granting institution. (2017). Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: pathology, assessment and management.

- Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. M. R. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Wolters Kluwer.

- Scott, A., Backman, L. J., & Speed, C. (2015). Tendinopathy: Update on Pathophysiology. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 45(11), 8330841. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5884

- Mellor, R., Grimaldi, A., Wajswelner, H., Hodges, P., Abbott, J.H., Bennell, K., & Vicenzino, B. (2016). Exercise and load modification versus corticosteroid injection versus ‘wait and see’ for persistent gluteus medius/minimus tendinopathy (the LEAP trial): a protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17(194), 196–196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1043-6

- Grimaldi, A., (2017). Conservative management of lateral hip pain: the future holds promise. British Journal of Sports Medicine; London, 41(2), 72-73. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096600

- Chowdhury, R., Naaseri, S., Lee, J., & Rajeswaran, G. (2014). Imaging and management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1068), 576–581. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131828

- Williams, B. S., & Cohen, S. P. (2009). Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome : A Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 108(5), 1662–1670. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e31819d6562