Low Back Pain: The Unrelenting Chronic Lower Back (Part 3 Pain Series)

Chronic low back pain describes pain in the muscles, bones, joints, and/or tendons of the low back that has persisted for more than 3 months (1). It is the 9th highest cause of disability globally, and accounts for nearly 20% of General Practitioner visits in Australia (2, 3).

Each person’s experience with chronic low back pain is unique, and is influenced by an interplay of physical, psychological, and social factors. These factors, as well as the mechanisms behind persistent pain in the absence of tissue damage, were discussed in detail previously in the “Making Sense of Pain” and “Managing Persistent Pain” articles (click to view). So if you haven’t read those, or need a refresher, we’d recommend heading back to read those articles before continuing.

For chronic low back pain, many different physical factors can exist, and may include underlying age-related changes, high cortisol levels from stress-inducing events, muscle weakness, physical deconditioning, poor sleep quality, poor diet, and increased body weight, among many others.

Regarding psychological factors, many have been linked to persisting high levels of pain and functional limitations in chronic low back pain. These include:

Pain catastrophizing behaviors (4)

Kinesiophobia (4)

Social Isolation (4)

Greater belief that pain will not improve (5)

Higher passive coping strategies (5)

Lower belief in pain self-management ability (5)

Anxiety (6)

Depression (6)

Reduced Openness to new Experiences (6)

Social considerations for those with chronic low back pain include, but are not limited to, financial stress from ongoing medical appointments, loss of hours and productivity at work, and strained relationships with work colleagues, family and friends (7). Those from lower socio-economic backgrounds are further shown to experience chronic low back pain at a higher prevalence.

Importantly, just because you have some of these physical, psychological or social factors, doesn’t mean you will go on to experience severe chronic low back pain. Just as well, even if you experience chronic low back pain, it doesn’t mean that all of these factors apply to your situation. Management of a person with chronic low back pain requires management of the whole person, and this will be different for everyone. The presence or absence of some of these factors can help to identify which management approaches will be most effective for each individual situation.

The following is a summary of recommendations taken from clinical guidelines that inform current best-practice management of chronic low back pain (7) :

| YES | NO | MAYBE |

| – Physical activity – Exercise – Pain Education – Psychological Interventions | – Routine Imaging – Ultrasound – TENS – Acupuncture – Kinesiotape – Osteopathic interventions – Traction – Laser therapy | – Manual therapy – Massage – Medication |

YES

An active approach combining physical activity, exercise, and psychological interventions is best for managing chronic low back pain (7). The best exercises are the ones that a person enjoys and can tolerate without experiencing a flare up in symptoms. These may be in the form of strength/resistance training, hydrotherapy, pilates, yoga, or walking. Pacing and Graded Exposure techniques, discussed in the “Managing Pain” article, can be used to help individualise exercise programs and progress physical activity appropriately. Regarding psychological interventions, strategies like goal setting and pain education aim to break down some of the psychological barriers contributing to a person’s pain experience. Helping re-shape someone’s belief that movement is dangerous for example, can increase a person’s willingness to try new activities (7).

NO

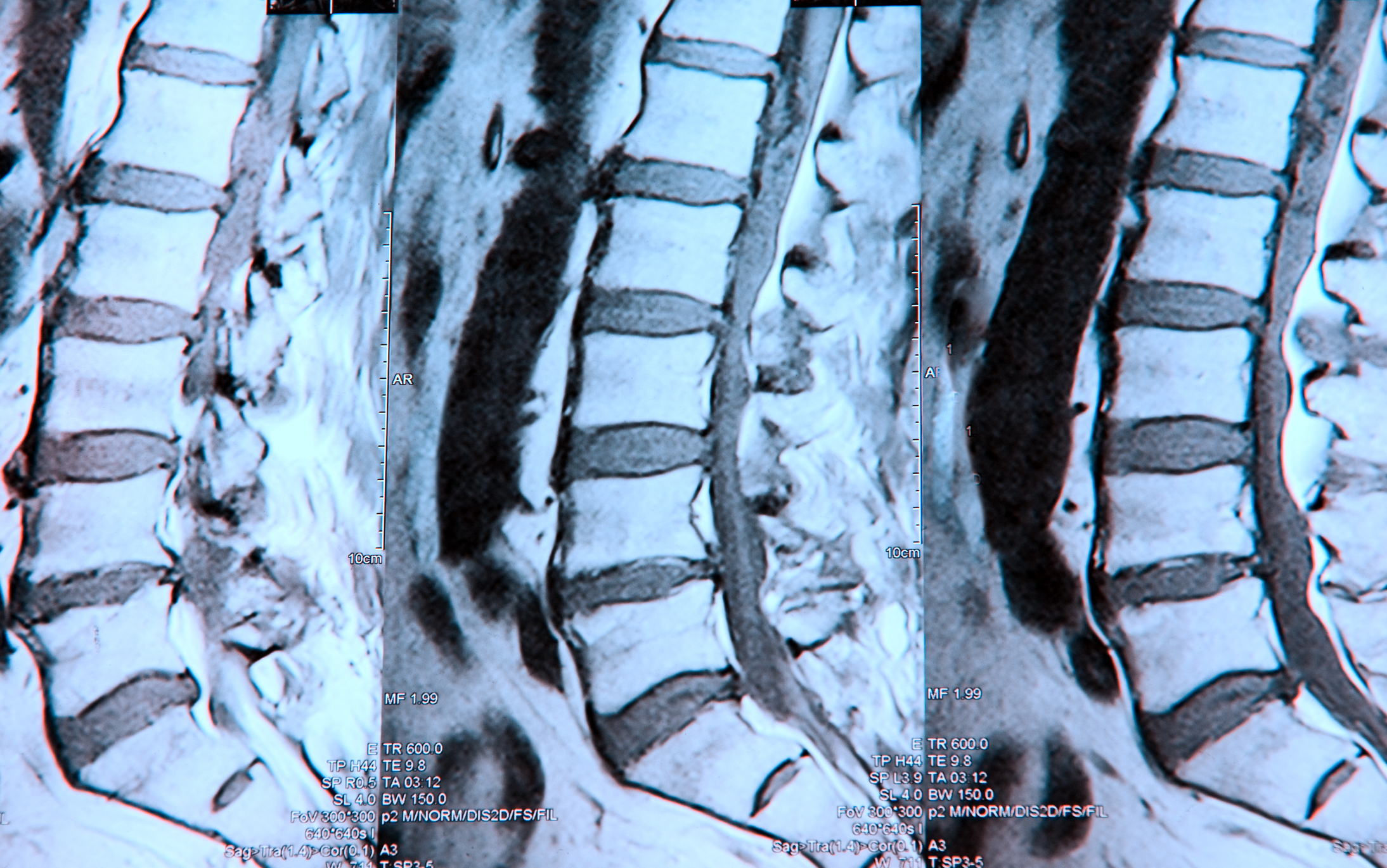

Despite best intentions of using imaging to clarify or confirm a diagnosis, imaging (radiology scan) reports can sometimes seem alarming, and their relevance can often be misinterpreted. This can reinforce the belief that one’s spine is damaged and make someone more fearful of movement. Imaging is therefore only advised in specialist settings, or when findings may change the course of treatment (8). All other treatments that are not recommended are ones that do not require active participation from the person receiving treatment. Research into these techniques show that they are either only effective in the short-term, or no more effective than placebo/sham treatments (for instance, getting pain relief from ultrasound treatment even with the machine turned off). Most importantly however, these treatments reinforce a passive role, where the therapist is doing something to the patient to “fix” something. This not only builds reliance on the therapist, but it can reduce one’s own sense of control and belief in the ability to self-manage one’s pain (7).

MAYBE?

Manual therapy and massage are not recommended on their own for the reasons explained above regarding passive treatments, however they can be effective when used in combination with exercise, education, and psychological interventions. Importantly, the role of massage and manual therapy is not to fix any broken structure, but rather desensitize tissues so that a person may become more engaged in exercise and activity (7). Medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are quite commonly prescribed, however since they primarily target the underlying biological mechanisms behind pain, and do not account for the other psychological and social factors contributing to the persistence of pain, effectiveness of medications for chronic low back pain can vary depending on a person’s individual circumstance. Therefore, it would be best to speak to a G.P. or pain specialist to determine what specific medications would be most appropriate.

Overall, if there is one thing to take away from this article series on pain, it is that pain is extremely complex. Many factors contribute to its development and persistence, and everyone experiences pain uniquely. Because of this, there is no one magic solution or quick fix for chronic pain. The pain experience is a long journey … a “continuum” if you will … that will be filled with ups and downs, so it is important to surround yourself with a team that can support you, listen to you, and provide you with the tools needed to navigate this journey.

Are you experiencing pain? Hit the ‘Book Now’ button below to book a time for physiotherapist’s so that we can offer help to you.

REFERENCES

(1). Nicholas, M., Vlaeyen, J. S., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Giamberardino, M. A., Goebel, A., Korwisi, B., Perrot, S., Svensson, P., Wang, S., & Treede, R. (2019). The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain, 160(1), 28-37.

(2). GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222.

(3). Deloitte Access Economics. (2019). The cost of pain in Australia. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-cost-pain-australia-040419.pdf

(4). Corrêa, L. A., Mathieson, S., Meziat-Filho, N. M., Reis, F. J., Ferreira, A. S., & Nogueira, L. C. (2022). Which psychosocial factors are related to severe pain and functional limitation in patients with low back pain?: Psychosocial factors related to severe low back pain. Brazilian journal of physical therapy, 26(3), 1-11.

(5). Chen, Y., Campbell, P., Strauss, V. Y., Foster, N. E., Jordan, K. P., & Dunn, K. M. (2018). Trajectories and predictors of the long-term course of low back pain: cohort study with 5-year follow-up. Pain, 159(2), 252–260.

(6). Ibrahim, M. E., Weber, K., Courvoisier, D. S., & Genevay, S. (2020). Big Five Personality Traits and Disabling Chronic Low Back Pain: Association with Fear-Avoidance, Anxious and Depressive Moods. Journal of pain research, 13, 745–754

(7). Malfliet, A., Ickmans, K., Huysmans, E., Coppieters, I., Willaert, W., Bogaert, W. V., Rheel, E., Bilterys, T., Wilgen, P. V., & Nijs, J. (2019). Best Evidence Rehabilitation for Chronic Pain Part 3: Low Back Pain. Journal of clinical medicine, 8(7), 1063.

(8). Wheeler, L. P., Karran, E. L., & Harvie, D. S. (2018). Low back pain: Can we mitigate the inadvertent psycho-behavioural harms of spinal imaging? Australian journal of general practice, 47(9), 614–617.